May 10, 2000

GAME THEORY

Making Hoop Dreams Come (Almost) True

By MARC SPIEGLER

|

|

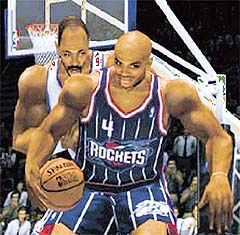

TELEREALISM

NBA 2K presents professional basketball as television

entertainment. A player can choose one of eight camera

angles to view the flashy offense or the more pedestrian

defense.

|

The National Basketball Association

was one of the marketing marvels of the 90's. So it is

no surprise that N.B.A. simulations have been a major

focus for video game makers, especially in an era when

motion-capture technology and high-speed rendering allow

the developers to offer nearly realistic games. Or rather,

"telerealistic" games, since television is the driving

medium behind the recent success of both the league and

the league-inspired games.

Many of today's basketball video games are licensed

N.B.A. products that feature full player rosters, with

images of the real athletes' faces skillfully mapped onto

their virtual bodies. At the top of this genre is NBA

2K, by Sega Sports for the Sega Dreamcast console.

Short of building in celebrity spectators and hordes

of photographers, every effort has been made to mimic

a televised event. The games start with laser-show introductions,

include a stream of cliché-ridden patter by the

television announcers for the Golden State Warriors, take

place in digitized versions of actual stadiums and even

include on-court woofing between players. When Kobe Bryant

pulls off a two-handed helicopter jam, for example, he

is prone to crowing, "I'm bustin' out the whuppin' stick."

To add to the telerealism, you can choose from eight

camera angles, including isolation cameras that track

a single character. Gamers can also call for a replay

at any moment. Using the console's controllers, you can

then watch the highlight frame by frame or freeze the

motion and swoop around the scene, recalling similar effects

in "The Matrix."

In actual game play, characters are impressively rendered,

their movements neither jerky nor truncated, and they

move around the court in an entirely plausible fashion.

The telerealism falls apart only in the close-up replays

triggered by players or by the game itself. That's when

the motions seem stiff and the players wear a single expression:

the patented sullen look of the professional athlete.

Only as their programmed shooting moves kick in do they

start displaying a wider range of facial expressions and

stop looking like doll heads on human bodies.

In fairness, that is a minor quibble, one that will

bother only players with unreasonably high standards for

the suspension of disbelief (and nit-picking critics).

Certainly, the game has a lot of what gamers call granularity,

those little details that make the action seem real. Would-be

coaches can call plays, change defenses and make substitutions;

fantasy-league devotees can trade players and even conduct

a full draft.

Game players with Dr. Frankenstein leanings can build

players from scratch, customizing things like height,

bulk and skills as well as facial hair, eyewear and sneaker

style. This character-making feature had one funny effect:

I built a player almost at random, then suddenly realized

that I had created a clone of Kurt Rambis, the gawky backup

center to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar during the Los Angeles Lakers'

"Showtime" era.

But once you get past all the razzmatazz, there is a

fundamental flaw in the game, one that has tripped up

the makers of every basketball game I have ever tried:

you just can't play good defense.

|

|

| Basketball with all the dazzle: no-look passes

and too-good-to-be-true dunks.

| |

|

|

Of course, that problem may be intractable. As anyone

who plays a team sport learns, the person playing offense

always has the distinct advantage of knowing where he's

going; the defender can only guess. That predicament is

compounded in video game play, where you can't watch your

opponent's hips or eyes, and where hitting a single button

will propel an offensive player toward the basket, but

adequately covering him requires a far more complex set

of moves. Because you can control only one character at

a time, you have to switch characters constantly as the

ball moves around the court, then move that man to the

ball quickly -- a tricky feat in the traffic of five-on-five

half-court offense.

That imbalance tends to make for riotously disjointed

games. On offense, you're pulling off plays you would

never attempt on a playground -- no-look passes, behind-the-back

dribbling, 360-degree dunks. And it takes only about three

attempts to learn the trick of successfully lobbing alley-oops

that lead to rim-crushing jams, an apparently unstoppable

tactic. Likewise, pushing the Turbo button while dribbling

upcourt tends to give you that extra quick step required

to shimmy behind your opponent for a layup.

Yet on defense, your character seems to be playing his

first game ever. If you want to win, you're usually better

off posting the man you actually control near the basket

to block layups and dunks, while letting the game's artificial-intelligence

programs handle the dirty work of actually guarding your

opponents. After a week of rigorous play, perhaps your

defense might become middling. But why bother, when you

can be competitive against the computer without even learning

to play solid man-on-man?

Without good defense, NBA 2K quickly becomes an exercise

in shame, as Rusty LaRue, the Bulls journeyman, grandstands

his way up the court after dunking over Glen Rice, the

Los Angeles Lakers All-Star (or, at least, over your sorry

attempt to play as Rice). The game has a practice mode

for passing and shooting, but not for defense. That is

especially disheartening because of NBA 2K's arsenal of

programmed offensive stunts.

One could argue that this is only fitting, given how

much of today's N.B.A. play revolves around making the

evening sports newscast with acrobatic slams and fancy

dribbling moves. And it is precisely the realism of those

components that makes NBA 2K such an exciting game to

play; there's no telling what wonder you'll pull off next.

Still, it's defense that wins real basketball games. As

long as virtual hoops draws more on the legacy of the

flamboyant dunkmeister Darryl Dawkins than the fundamentals

fanaticism of the great U.C.L.A. coach John Wooden, there

is some critical realism sorely missing. Then again, it's

just a video game -- cue the highlight reel.

NBA 2K by Sega Sports for Sega Dreamcast; $39.99;

for all ages.